dbms- transaction

Table of Contents

Definition⌗

A transaction in DBMS is a finite sequence of database operations that is executed as one logical unit of work, meaning either all operations are performed successfully or none are performed.

-- Example for "logical unite of work"

Read(A)

A = A − 100

Write(A)

Read(B)

B = B + 100

Write(B)

Commit

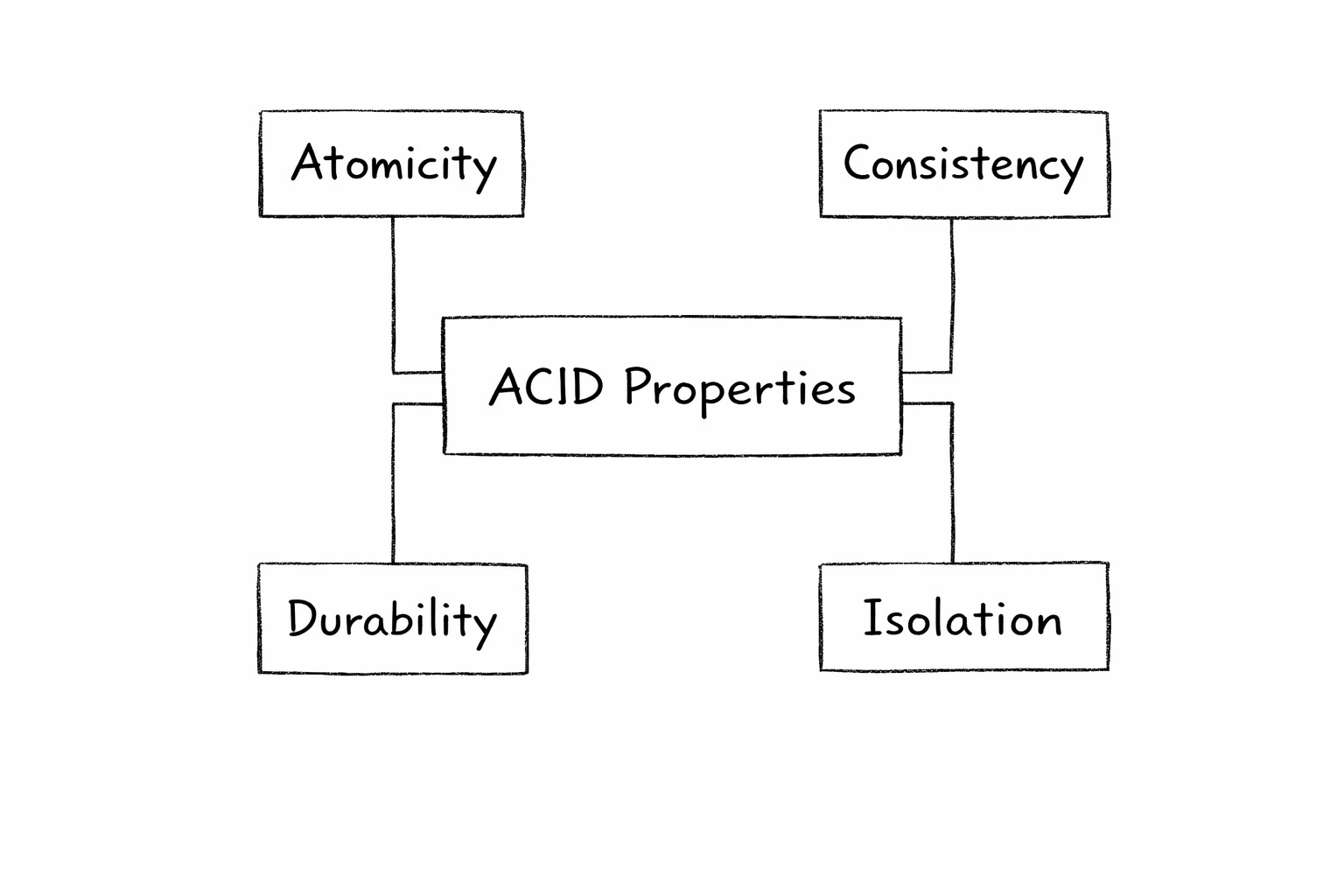

A transaction must satisfy the ACID properties to ensure database correctness and consistency.

Key Points⌗

- A transaction groups multiple database operations into a single logical task

- Partial execution is not allowed

- Failure of any operation causes the entire transaction to rollback

- Ensures reliability in concurrent and failure-prone environments

ACID Properties (Overview)⌗

- Atomicity – All operations execute or none execute

- Consistency – Database remains in a valid state

- Isolation – Transactions do not interfere with each other

- Durability – Committed changes persist permanently

Schedule⌗

A schedule is the execution order of operations of multiple transactions on the same database, possibly executed concurrently.

Why Concurrency?⌗

- Improved throughput{no. of lines executed per unit time}.

- Resource utilization.

- Reduced waiting time.

Problems with Concurrency⌗

- Recoverability problems –> Occur when a transaction commits after reading data written by another uncommitted transaction, which may later be rolled back, leading to inconsistency.

- Deadlock –> A situation where two or more transactions wait indefinitely for each other to release resources, causing none of them to proceed.

- Serializability(serial flow execution) issues –> Arise when concurrent execution of transactions produces results that are not equivalent to any serial (one-by-one) execution, leading to incorrect database states.

Serializability Issues⌗

- Lost Update Problem – Updates of one transaction are overwritten by another.

- Dirty Read Problem – A transaction reads uncommitted data of another transaction.

- Phantom Read – Re-executing a query returns extra or missing rows.

- Unrepeatable Read Problem – Same read gives different values due to another transaction’s update.

- Incorrect Summary Problem – Aggregated results are computed on partially updated data.

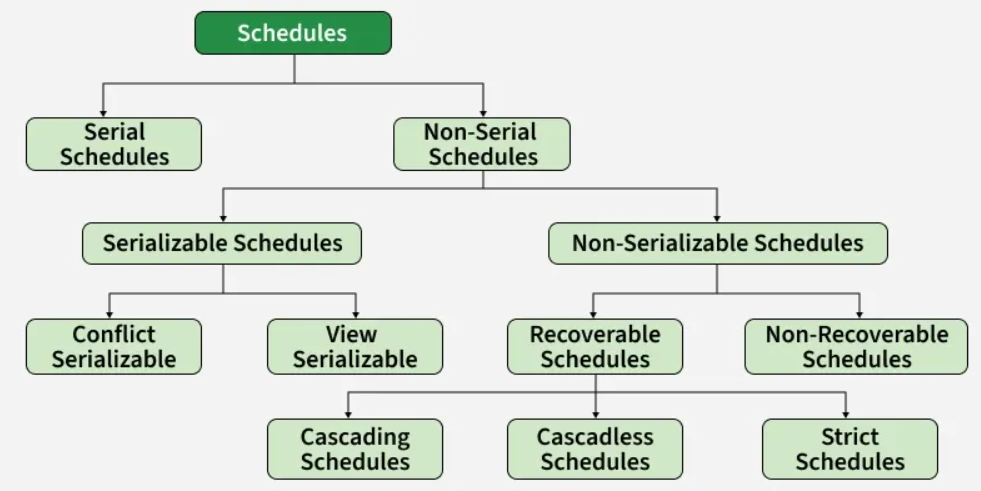

Types of Schedules⌗

- Serial Schedule

- Non-Serial Schedule

- Serializable Schedules

- View Serializable

- Conflict Serializable

- Non-Serializable Schedules

- Recoverable Schedules

- Cascading Schedules

- Cascadless Schedules

- Strict Schedules

- Non-Recoverable Schedules

- Recoverable Schedules

- Serializable Schedules

Serial Schedule⌗

Each transaction will run one by one without any interference(overlapping).

Eg: you don’t start new transaction until the current one is completely finished.

Number of Serial Schedule = n! // {n factorial}

Non-Serial Schedule⌗

Multiple transactions are allowed to interleave, means transaction overlapping is allowed. Eg: banking system.

No. of Schedule Possible =

[(n1 + n2 + n3 + n4 + . . . . . . Nn)! ] / [n1! n2! n3! n4! . . . . . Nn!]

Serializable Schedules⌗

A concurrent(interleaved) schedule which provide result as a serial schedule.

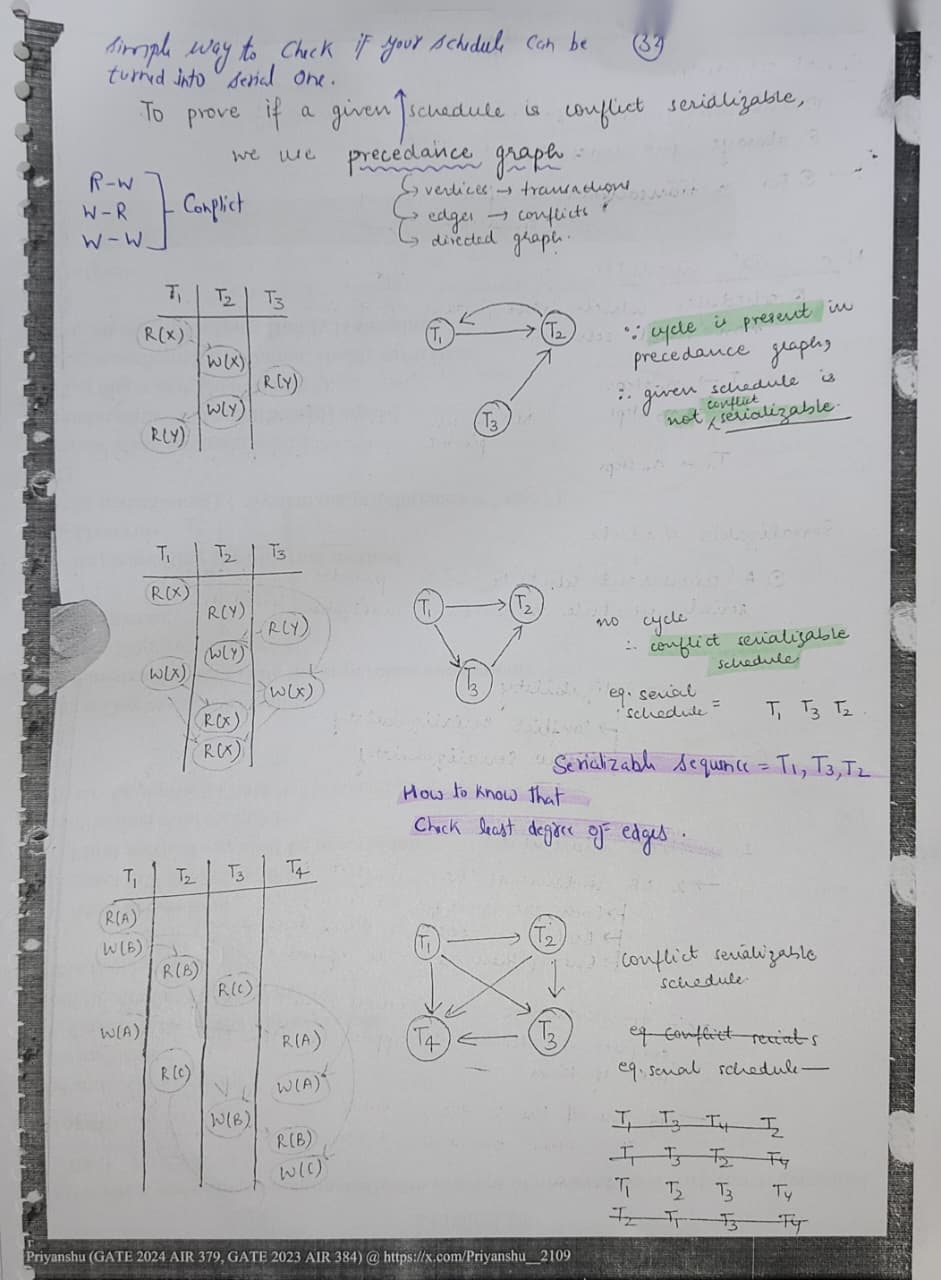

Conflict Serializable Schedule⌗

Its a type of a validation through which we can check if a schedule is serializable, if yes then for which sequence we can say it’s serializable. If a loop occur in conflict then we can’t tell if schedule is serializable. {In this case View Serializability is used.}

View Serializable Schedule⌗

We check view serializability if

- Loop is there in precedence table means not conflict serializable.

- If there is no blind write, means no write happen without a read.

Steps to check view serializability:

- Who reads first from db.

- In between reads are same.

- who write last. If all 3 above are equal in both schedules, then we can say both schedule are view equivalent.

Non-Serializable Schedules⌗

Non-serializable schedules are interleaved(mixed) sequences of transactions that can’t be rearranged into any serial order without causing inconsistencies.

Recoverability Schedule⌗

A recoverable schedule is one in which a transaction only commits after all transactions whose changes it has read have also committed.

Example: If transaction T_i reads a value written by transaction T_j, then T_i must commit only after T_j commits to ensure no rollback of a committed transaction is needed.

Cascadeless recoverable schedule⌗

a transaction can only read a value if the transaction that wrote or modified that value has already committed. If the writing transaction hasn’t committed yet, then the reading transaction simply waits and does not read that value.

Cascading recoverable schedule⌗

A cascading recoverable schedule is one where transactions can read uncommitted data from others. If the original writer transaction is rolled back, any transactions that depended on that uncommitted data may also have to roll back, creating a cascading effect. However, no already committed transaction is undone in this process, so the schedule is still considered recoverable.

Locking Protocols in DBMS⌗

In database systems, locking protocols manage concurrent access to data. Two key types of locks are:

Shared Lock (S-lock)⌗

- Allows multiple transactions to read the same data item concurrently.

- When a shared lock is set, other transactions can still read but cannot write to that data item.

Example: Imagine two transactions, T1 and T2. Both want to read the same record from a table—say, a customer’s profile. T1 places a shared lock on the customer record. While T1 is reading, T2 can also place a shared lock and read the same record at the same time. Neither can modify it until those shared locks are released.

Exclusive Lock (X-lock)⌗

- Allows a single transaction to both read and write to a data item, preventing others from accessing it at the same time.

- This lock must be released before other transactions can access the item.

Example: Now imagine T1 needs to update that same customer record. T1 places an exclusive lock on the record. While T1 holds this exclusive lock, no other transaction (including T2) can read or write to that record until T1 finishes and releases the lock.

Starvation and Blocking⌗

-

Starvation: A transaction might starve if it waits indefinitely for an exclusive lock because other transactions keep holding shared locks.

-

Blocking: If a transaction is blocked for an exclusive lock by multiple shared locks, it can’t proceed until those shared locks are released.

Lock Upgrade and Downgrade⌗

-

Lock Upgrade: Switching a lock from shared to exclusive if a transaction needs to go from just reading to also writing the data.

-

Lock Downgrade: Changing a lock from exclusive back to shared if the transaction no longer needs to write, allowing others to read.

Unrepeatable Read Problem and Two-Phase Locking (2PL)⌗

Problem (Unrepeatable Read):

- In normal locking, a transaction might read a value, release the lock, and then another transaction changes that value before the first transaction reads it again, resulting in a different value the second time.

Solution (2PL):

- With two-phase locking, a transaction acquires all needed locks first (growing phase) and only releases them at the end (shrinking phase), preventing changes by other transactions in the middle. This keeps the value consistent for the entire transaction.

Every schedule which is allowed under basic 2PL is conflict-serializable.

Question:

Consider the following schedule involving two transactions T1 and T2 on a single data item X:

-

T1 locks X (read lock), reads X.

-

T1 unlocks X.

-

T2 locks X (write lock), writes to X.

-

T2 unlocks X.

-

T1 locks X again (read lock), and reads X again.

Is this schedule allowed under basic two-phase locking (2PL)?

Answer:

No, this schedule is not allowed under basic 2PL. Under 2PL, once a transaction starts releasing its locks (enters the shrinking phase), it cannot acquire any new locks. In this schedule, T1 releases its lock on X and then tries to lock X again later. This violates the two-phase rule.

Problem with Basic 2PL⌗

Basic two-phase locking can suffer from two main problems: starvation and deadlock. Additionally, it can sometimes allow non-recoverable schedules.

Strict Two-Phase Locking (Strict 2PL)⌗

-

Definition: A concurrency control protocol where a transaction holds all exclusive locks until it commits or aborts.

-

Example:

- T1 locks and writes to X.

- T2 and T3 wait until T1 commits.

- After T1 commits, T2 and T3 can then access X in sequence.

-

Benefits:

- Maintains data integrity by ensuring all operations are completed before locks are released.

Rigorous 2PL⌗

- Definition: Both shared and exclusive locks held until commit.

- Locks: No locks are released before commit, ensuring stricter consistency.

- Pros/Cons: Strongest consistency, no uncommitted data read; lower concurrency since all locks are held until commit.

Topics Covered in Hierarchical format⌗

Schedules

│

├─ Serial Schedules

│

└─ Non-Serial Schedules

│

├─ Serializable Schedules

│ │

│ ├─ Conflict-Serializable Schedules

│ │ │

│ │ └─ Lock-Based Protocols (ensure conflict serializability)

│ │ ├─ Basic 2PL

│ │ │

│ │ ├─ Strict 2PL

│ │ │ └─ (also ensures Strict & Cascadeless schedules)

│ │ │

│ │ ├─ Rigorous 2PL

│ │ │ └─ (stronger than Strict 2PL)

│ │ │

│ │ └─ Conservative 2PL

│ │ └─ (deadlock-free)

│ │

│ └─ View-Serializable Schedules

│ └─ (superset of Conflict-Serializable)

│

└─ Non-Serializable Schedules

│

├─ Recoverable Schedules

│ │

│ ├─ Cascading Schedules

│ │

│ └─ Cascadeless Schedules

│

└─ Non-Recoverable Schedules